In 2021 we brought you exciting news of a $5,000 Community Impact microgrant awarded to our partner, Hope for Girls and Women by Open Map Development Tanzania (OMDTZ) which was to be used to support with leveraging the use of OSM and mapping to help solve community challenges.

Hope for Girls and Women chose to use the grant to:

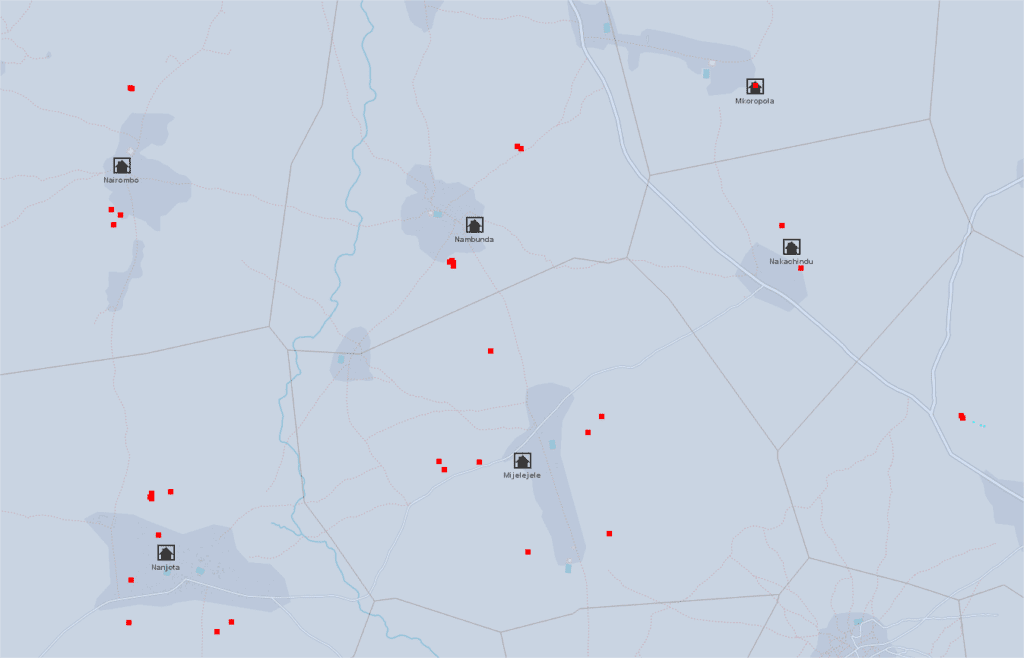

- Expand the existing OSM community in the Serengeti region

- Add healthcare facilities to maps, helping the local community in the process

- Collect information about local schools

- Add other features available in the villages as and when they were encountered during field visits

Challenges mapping health centres in Serengeti

The initiative brought with it several challenges and obstacles that needed to be overcome with a strategic approach, taking into consideration the available resources, budget and location of health care facilities. These challenges ranged from:

- Mapping contributors not having the necessary equipment to submit data. There was a lack of laptops or smartphones at times

- Reluctance by private health care centres and laboratory managers and teams to support and collaborate with us by providing information about their sites. At times concerns would take upwards of an hour to resolve with site owners, which added to our timeline

- We were delayed starting training by two months, this meant we had to spend significant time on refresher sessions for participants

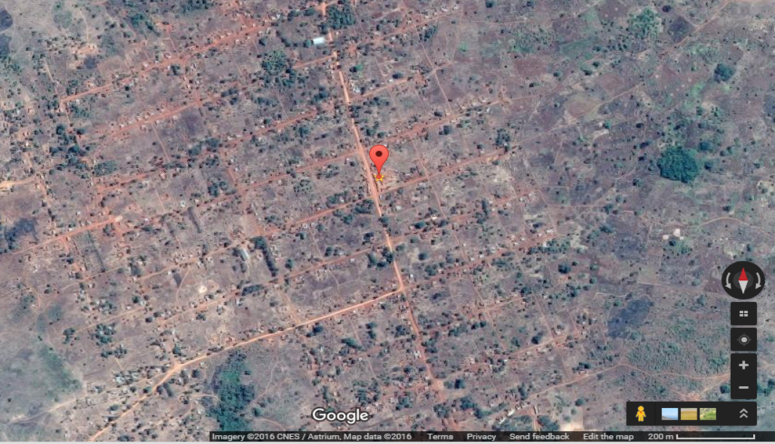

- Locations of villages in Serengeti can be very remote and with large distances between one another. Couple with very rainy and wet conditions, this added time and difficulty as well as costs to several field visits

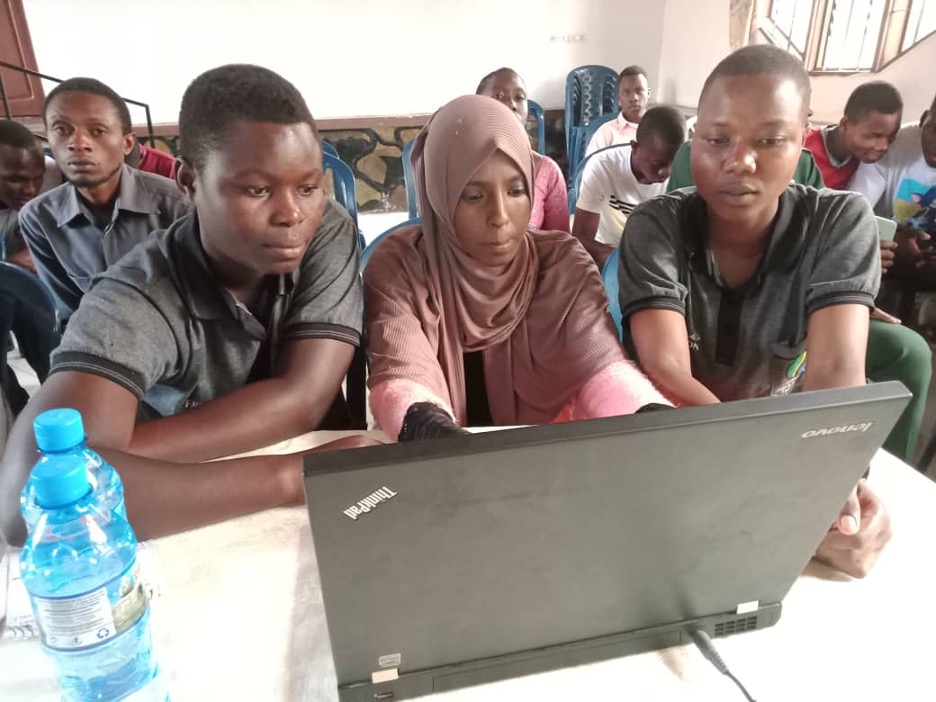

We were successful in involving 35 new local mappers across Mugumu, Serengeti, and trained them on the use of Open Data and how to use it to solve community challenges. This was well received, and we are confident we provided a level of training and expertise, as well as insights and real life working examples to ensure that those involved will continue to not only take an interest in mapping, but also actively participate in mapping moving forward.

Outcome of the health care mapping initiative

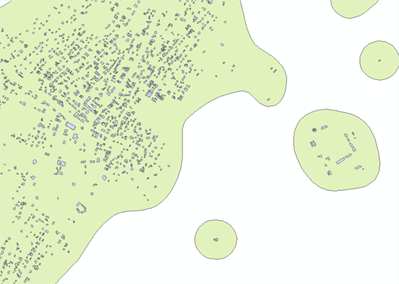

We added the following facilities to maps of Mugumu, Serengeti:

60 Health center facilities where;

- 2 are Hospitals

- 15 are clinics

- 35 are pharmacies

- 8 laboratories

Collaboration and training across the following partners:

- MARA RED CROSS: a team of five people participated, building their capacity and understanding on the use of Open Data, we also involved them in the whole process of contributing to mapping activities and improving knowledge on how mapping can help them with solving community challenges. We also agreed to keep sharing our insights on mapping and other related activities that will help the community

- SETCO Youth Mappers: 10 Youth mappers were involved in this initiative, which opened their eyes to how they can use mapping to solve community challenges. This will trigger them to be more enthusiastic when identifying ways of using the knowledge acquired. The easy access to health data is helpful because we need this information to be freely accessible to give the community added support

Hope for Girls and Women Tanzania: 5 girls from Hope learned how they can contribute to impacting the community. For some of the girls who are pursuing careers in community development, this was great experience and a dream come true.

Hope for Girls and Women often takes girls to obtain health services, so moving forward it will be possible to participate in updating health facility locations and information and have a better understanding of the procedures of mapping and collecting helpful health information. This also further adds to the positive impact Hope for Girls and Women is having on the local community around Serengeti and Butiama

- Community Involvement: 5 participants from the Serengeti community were actively involved. It is important to pass on knowledge about mapping and how mapping can help in solving community challenges, especially as these people are often the users of such data. The ongoing strickle effect of sharing new-found knowledge with other people in the community is an additional benefit of training individuals and small groups.

- Local Government: We were happy and grateful to have the Deputy District Community Officer and Chairman to participate in the mapping training, helping them to better understand the importance of mapping, how it helps community development and even their own work

What has the impact of the OSM microgrant and associated training been?

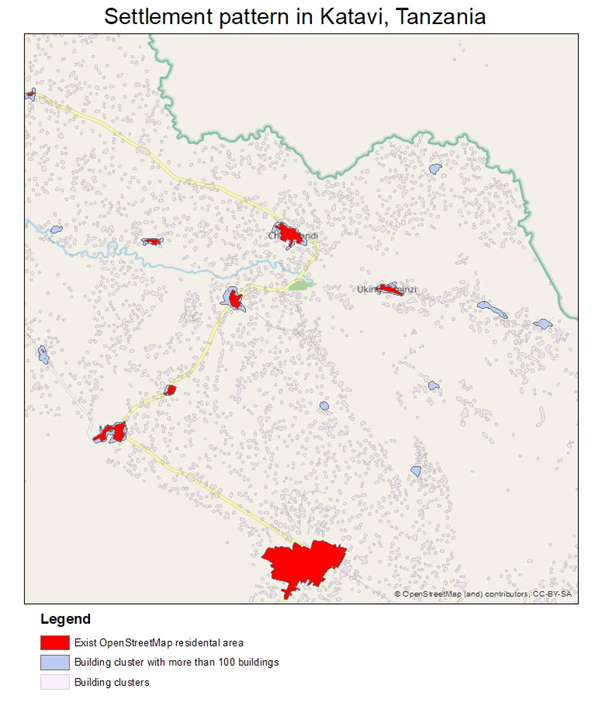

The Serengeti community will have an easy way of accessing health center facility data. Hope for Girls and Women Tanzania will also be identifying which health center facilities are available 24 hours a day, and what kind of services are offered at specific health centers

Involving local government officers, village chairmen, and community people, Youth Mappers and other NGOs has helped to raise awareness and interest in using Open Data to solve community challenges. This helps to scale up the knowledge within such groups and also increase contributors and proactivity around mapping.

Having access to health data shows a picture of the local infrastructure, and allows us to better demonstrate challenges in the community whereby people suffer from a lack of access to health centers. Providing evidence of how far individuals have to travel to find sites, availability of services and staff and opening hours, can be a much needed wakeup call for the Government to finding a solution to reducing the challenges that Serengeti people are facing.

The Villages Chairmen has requested maps showing all features available in their villages in addition to maps which focus on health centers and schools, so we have agreed we will do a participatory mapping in each village, so we people with further training. In return, villages can provide information which we can use to create maps with more details in each village.

We will continue to bring you updates on further mapping projects as they arise. If you have a mapping project that you think could benefit northern Tanzania, and/or if you are aware of grants for such projects, please do reach out to us here.